I also realized that because I did not have a blog, I could only comment on other submissions. So back on Monday night, I started this blog so I can share my thoughts.

No matter how imperfect or juvenile the style, no matter how fawning I may inadvertently appear to be, regardless of the potential unpleasantness of the sickeningly sweet taste of my words to a reader who might consider it to be a puff piece, I'm going to paddle out into the water with my mind, an alphabet, and my heart and start riding the tides....

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Part One

A quick look at the train station shootout sequence in Brian De Palma’s film The Untouchables

The production team -

Directed by Brian De Palma

Produced by Art Linson

Written by David Mamet

Original Music by Ennio Morricone

Cinematography by Stephen H. Burum

Film Editing by Jerry Greenberg and Bill Pankow

Production Design - Patricia Von Brandenstein

What follows is an attempt to provide some personal observations about De Palma’s use of numbers and visual storytelling in The Untouchables. My favorite De Palma films tend to be the ones that he has written and directed. I enjoy his work in general. I have always felt that De Palma has been mistreated, mischaracterized and discarded in print or online without being recognized for using the gifts and talents that he employs in his films.

We all know the line about opinions being like @$$holes because everybody has one.

My agenda, if there is one, is to offer a sincere appreciation of his communication skills as a filmmaker. An artist's work should speak for itself. No matter how gifted the creator may be, if the audience does not bring intelligence and an open mind to the encounter with the art, or a willingness to think about and try to understand what they are seeing or hearing, negativity ensues. If the audience is a co-creator in the creative dialog with the artist and they shirk the responsibility of thoughtful analysis, then meaning becomes meaningless and we all lose. I believe De Palma is a terrific artist who continues to be deserving of a much greater recognition and appreciation within his lifetime by film lovers throughout the world.

Anyone who has seen the Martin Ritt film Cool Hand Luke remembers the classic line delivered by Strother Martin when he says “What we have here..........is a fail-ure....to com-mun-i-cate."

If you want one top example of how to achieve successful communication via a tense suspense film sequence, I recommend viewing and reviewing the train station sequence of The Untouchables. When you examine it, “what we have here” is a masterful ability to communicate a rich, multi-layered, elegant delivery

of visual and aural information. It is thrilling, beautifully simple and quite complex all at the same time.

The train station sequence works on a number of levels but mainly because of the effective direction and conceptual choices realized in the editing - a structural game plan exploring timing and the plasticity that can be employed in filmmaking. In order for the editing to work, you have to have it on film.

All filmmakers have the same toolkit. Anyone else can do the same things, but can they do it as well?

The box office and the reviews embraced the picture and the success of the film is due to the high level

of the ideas at work, the production team and certainly there can be no denying that Ennio Morricone’s score played a great role in making it a wonderful film. In my opinion, he should have won the Oscar for The Untouchables as the best score in 1987. The triumphant music throughout the film, and especially the terrifying lullaby used in the train station steps sequence, represents everything that has ever been superior about experiencing and enjoying a Hollywood movie.

Scene summary

Ness and George Stone arrive at the Chicago train station minutes before 12 o’clock AM. They are seeking to arrest Al Capone’s accountant Walter Payne before he gets away on the 12:05 train to Miami. It is essential that they bring him into custody, and gain his testimony to enable the conviction of Al Capone on charges of tax evasion.

At approximately 86:23 into the movie, Ness and Stone enter through the doors into the train station interior.

The next scene change to the courtroom interior occurs at 95:52.

The actual train station sequence lasts about 9 minutes and 29 seconds which rounds off to 9 ½ minutes.

The train station clock initially indicates 11:55 PM, and the train will depart at 12:05 AM so we have a ten minute window of opportunity – five before and five after. As the sequence runs thirty seconds shy of ten minutes, the screen time is very close to approximating real time.

The sequence relies on what is there: ideas, editing, pacing, music, sound effects and content, and it relies on what isn’t there: dialogue. It is ultimately, essentially wordless because the scene is developed so that a range of dynamics is explored and built from the ground up. The sound effects are spare, the music is hypnotic, or like a reverie, or a lullaby, or horrific as needed, and the dialogue is minimal.

It is eventually removed for the final third, which makes it virtually a silent film with sound effects and music. The dialog returns in time for the showdown with the character Bowtie Driver who has a gun to the head of the bookkeeper. Whatever dialogue is in this sequence is short and of consequence.

Moving outside to inside

Note the dialogue that occurs immediately before the end of the scene that leads to the train station interior sequence. (Note: This is my translation/approximation of what occurs and not the actual screenplay)

EXT. TRAIN STATION WALKWAY - NIGHT

A tracking shot moving backwards frames Ness and Stone

walking briskly side-by-side upon a corridor path towards the train station door entrance.

To their left is the exterior wall of the building, to their right a row of massive columns.

NESS

The bookkeeper is no good to us dead.

(STONE walks in silence)

NESS (cont’d)

(turns to address Stone)

Stone?

STONE

(beat)

Yes sir.

The scene before the interior of the train station sequence is communicating a number of things but specifically to this viewer, it is an ongoing visual countdown of 3-2-1. Three windows and three lights above, two windows with no meaning and two men driven to give meaning to both the living and the dead, one window of significance and one purpose shared by the team.The timing of this take allows the camera frame to show three windows pass in succession on their left as Ness and Stone are walking forward. The first two are empty. The third contains a cross framed within it. It is seen just prior to hearing Stone’s reply “Yes sir.” In the frame grab above we can see three lamps, two men, and a cross contained within one window: an important split second moment that is frozen in time allowing us to see the arrangement of a 3-2-1 countdown being conveyed.

The intersection of a vertical axis and a horizontal axis creates an intersection that can be visually interesting.

As we observe what we see contained within the screen of the movie (or a TV or a painting or a photo or an illustration) we decide what is of importance to us. The creator of the art decides for us what to include or not include that will provide materials for the viewer to decide how to piece together meaning in a satisfying way.

The cross is a unique form made up of an element - the line - that is presented twice in a union: one horizontal line position with a second vertical line positioned at a 90 degree angle to the first line and superimposed over it. They are joined at the midpoint of each line.

The window with the cross is an instance of a form

that offers an attraction to the eye,

and it gets our attention,

if and when it is recognized by the viewer as being of interest.

That intersection can have different meanings to different people depending on the context of the film, and the internal reference bank of the person. It could be the cross-hairs of a sniper scope, it could be a visual entrance towards seeing a vanishing point, it could be a sign of death, it could work in conjunction with other information being conveyed so that meaning or understanding or meaning can be increased or enhanced or underlined. It could be just an X that your eye does or does not notice.

If we take a cross form and turn it 45 degrees it becomes an X.

We know that when we see an x it could mean many different things.

A few of the meanings could be

- "x" marks the spot

- X is well known as the rating code for films with adult content

- XXX is poison - or really intense pornography

- X is ten

- X can be an abbreviation for the drug ecstasy

- X can mean “(e)x” as in my ex-husband or ex-wife

An X can simply be a message to pay attention or encourage interaction between the viewer and the screen.

X can often mean a change or a reversal of fortune when it is curved and used as a visual form in movies.

That's not the only meaning that it has but I've seen it many times.

Such as:

- The curved rungs of the ladder by the pool when Fredo's life is about to change in Godfather II.

- The tubes that are attached to the bathroom handheld showerhead in Femme Fatale.

- The purse straps of Marion's handbag in Psycho.

If there is a conscious decision by the filmmakers to manipulate shapes as a strategy to be developed in a film, as shapes are used and changed in a film we can see the story and the characters in them change as well.

Being that the window with the cross is different from the two that preceded it, we know that although it is the same form, it is different and potentially it can offer a new meaning by the juxtaposition with the other windows.

Picture and sound and dialog and story and effects and music can make up a film. Underneath the uppermost layer of what we see are some essential building blocks of shapes and numbers and letters which also convey or reinforce information and meaning. Through the introduction and alignment and rearrangement of forms as shapes and numbers and letters into the screen frame, this production design/art direction/directing thread of conveying meaning is evident and essential to storytelling in film.

Although I have seen The Untouchables more than a few times, I only saw the cross in the window detail for the first time when I decided to revisit the steps sequence for my class.

Seeing the windows in sequence 1-2-3 is not only just that, by the filmmakers choosing to show that sequence, and by our seeing that sequence, we are referencing any or all of our other life encounters with other films, and a sequence of numbering 1-2-3. If we notice it as it happens, or if we subconsciously read the layering being conveyed visually, it can assist in our comprehension. Even though this may be obvious to some, it is not obvious to others who watch films and it remains a delightful and intriguing aspect of film craft to me.

Cross in window makes you think of.....Psycho?

If we see the cross, when we see the cross in that window outside the train station framed within the "window" of the movie screen in The Untouchables scene, we might be inclined to choose the moment in Psycho that occurs in the first interior scene of the movie as we are introduced to Marion and Sam near the end of a midday lover's tryst as one of our reference points.

The dialog and the information being conveyed show us the intimacy and guilt and anxiety that are shared by a man and a woman who are in love and dissatisfied with their lives.

Visually we are aware of window blinds and a mirror and windows. The basic shapes are emphasizing

vertical lines, horizontal lines and squares and cross forms. We see triangles in mirror symmetry upon the straps of Marion's bra. These characters are half-undressed which indicates lovemaking and the degree to which we are privy to the secret hidden inner meaning and thoughts that exist within their lives, knowledge that will need to be clothed or hidden so that they can make their way safely back into anonymity. We see them inside before they will return outside.

As that scene builds, we will see and recognize these lines and forms and store them away for assembling meaning. The visual lines individually and together along with the dialog develop interest and meaning that is built ultimately into an awakening by the viewer.

Marion is indeed late - she will soon be dead.

Sam will have to put his shoes on to go and search for answers in the disappearance of Marion.

Sam looking sadly at his feet is a universal situation that everyone can feel when love has left us.

However there is more to it than that.

Although Sam is seen as a stronger slightly taller man than Norman Bates, he is a double to Norman in appearance as one of the mirroring elements in the story is explored. Because of this similarity, Sam looking down at his feet is also a parallel to the situation that has initiated Norman's actions in the past and it is an ongoing relationship in the present tense of the story when Norman changes back and forth between two sides of one form.

When we see Sam as a man left alone by Marion,

we will also be seeing an understanding of

Norman - a man who is left alone by a woman (his mother who loves him.)

This is an essential first step to understanding that Norman is around when his Mother isn't.

Conversely Mother is around when Norman isn't.

Because Norman is neither woman nor-man. He is both.

appears slightly larger than the other two numbers.

This figurative alignment suggests a ratio of 5 to 4 or a relationship of 5 -1- 4.

If you subtract the numbers five minus one = four and that is exactly the operation that will be performed in the fruit cellar basement climax of Psycho.

This is visual filmmaking in action and Hitchcock is not only known as the master of suspense, he is a master of visual storytelling and Brian De Palma in his interviews always acknowledges this. Anyone who wants to understand visual storytelling must analyze Hitchcock.

Returning to Ness and Stone passing the windows outside the train station, even though the screen grab is a frozen moment that will zip by when played in real time, I find it of interest because of the saying - the devil is in the details.

Sometimes there are happy accidents that occur in production, and every plan needs to be adjusted

when something goes wrong, and it is inevitable that in each day there are many things that will not work or go as planned. Minimizing errors and mistakes and day-to-day damage control creates a final product that becomes whatever it was supposed to be, and it will be something different than the original conception.

That being said, it is still the case that the production team on a film achieves many or most of the goals of intended content and messages showing up on the screen.

Moments like the cross within the window frame can be seen as offering subliminal meaning on a first viewing, or an idea whose meaning becomes clear on an additional viewing, or you can discard that idea as meaningless. Our senses record and comment upon everything we see, as well as the details that we did not realize that we have seen. It doesn't matter if we are considering a box office smash or a popcorn film, or an art film or a good film or a bad film, when one makes an evaluation of quality or craftsmanship or value of a finished product, it is important to seek out what works and what doesn't. The slightest and smallest detail can wreck a project. It can also be one link in a chain reaction of ultimate meaning that can create a huge pay off for the audience scene-to-scene and over the course of the entire picture.

The medium tracking shot shown in the frame above

cuts to a wider perspective (shown below)

where Ness and Stone turn left to enter the doors side-by-side.

As they open the doors in tandem, we perceive a visual confirmation,

a period being placed at the end of a sentence that communicates

through dialog and visuals that they are a team, and they are in sync.

Also of note is the signage above the three sets of double doors: TO ALL TRAINS

After you watch the train station sequence play out, a review of the sequence and the dialog shows that those three lines are not only a declaration of intent and a reminder to the characters, more importantly they are directions to the viewer that is telling us that literally Stone will be the man responsible for delivering the shot that will take down the Bowtie Driver at the end of the sequence.

We receive the same information in two ways.

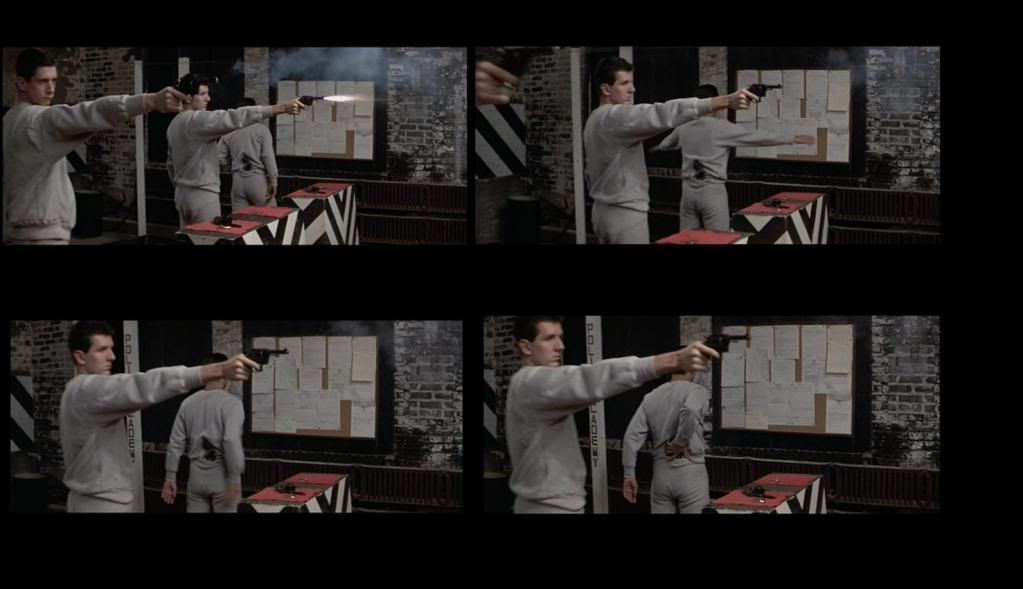

We hear the sequence of six shots ( 1-2-3-4-5-6)

as well as see the shots delivered

in three shots to the center of the stomach area of a target

in three shots to the center of the stomach area of a target

followed without a break by three shots to the head area of the same target.

The two tilting shots in a subliminal sense are the opposing forces at play being equalized as they cancel each other out.

To All Trains

Here is another instance where you might say this is my overreaching to prove a point.

As always, I see something that I want to share that may or may not be insightful - so here it is.With the death of Malone +Wallace we have two pairs left alive

ALL - The total of the people there, most of whom seek to arrive or depart. The ones who are killed will arrive and depart.

TRAINS - The goal of the Capone gangsters to put the bookkeeper on the train

An office door reads 222 which totals SIX - or three instances of two

Visually we see three instances of the number two and a single man

3-2-1

(which sounds like 3 to 1 or it might be nothing at all.....)

Parallel to Hitchcock and an example of his use of teamwork with numbers

Psycho is endlessly fascinating for many different reasons. The film succeeds by delivering content and information through incredibly efficient and compelling story construction, the direction, the editing, the music, and the acting. It is difficult to make any film. It is hard to make a good film and harder to make a great one. Making a masterpiece seems an outrageous proposition but occasionally it occurs. Hitchcock comes along and makes many fantastic films, and as one of the greatest icons in film, he starts hitting his stride operating on all cylinders: Strangers on a Train, Rear Window, Vertigo, North by Northwest, and Psycho.

Success leaves clues and his films are entertainments that can also be seen as exercises in how to make films and communicate with the audience. Given his self-imposed restrictions on budget and the challenge to show other "wanna-be" filmmakers how it is done, with Psycho Hitchcock rolled the dice and hit the jackpot. The payoff continues to hit year after year because people who love films and filmmaking return again and again to learn. The film soars and escapes the confines of budget because it radiates with IDEAS integrated at every turn of the storytelling in ways that support or uplift the delivery of the content and do not get in the way of the experience.

Once a person becomes enamored and entranced by the universe of ideas and the execution of ideas in Alfred Hitchcock films, it should be no surprise why Brian De Palma, and every other film director and movie fanatic would become obsessed with symmetry and construction and form in Hitchcock. As an example of numbering in Psycho that I really enjoy is the way Hitchcock and company have Sam and Lila move through the Bates Motel walkway by the cabin doors and then back again.

Showing them walking to their cabin (initially from Norman’s viewpoint within the covered area of the walkway) and then walking away from their cabin (shot from an objective viewpoint in the parking area) is a method of defining the architectural space and the walkway itself. Lila’s choice to then go off the path which was just visually established is a wonderful breaking away from restrictions. Just as Marion went off the moral path of life and drove off of the main highway to her eventual death, Lila too goes off the path in a breakthrough moment by being driven to find the answer to Marion’s disappearance. Lila has chosen an access point which has always existed in the film but was only hinted at previously when we see Norman driving Marion’s car as it exits frame right on her voyage to the swamp via the trunk.

The countdown of cabin numbers behind Sam and Lila prepares us for the excitement that will be experienced by the viewer and by Lila as she makes her ascent up the hill via the back path in a cross-cutting of ten shots seen from her POV and ten objective shots. Then of course we have the basement payoff of numbering that follows the exploration of the three floors of Norman’s house.

The De Palma-Hitchcock connection is always referenced by fans or critics when considering films like Sisters, Obsession, Dressed to Kill, or Body Double. The connection is usually not referenced in a discussion of The Untouchables because attention has always focused upon the obvious inspiration of using Eisenstein's Odessa Steps sequence from Battleship Potemkin. I am bringing attention to the pairing of Sam and Lila at the Bates Motel and the pairing of Ness and Stone upon the steps of the train station because these are two ideas which are related but different.

In Psycho when Sam and Lila appear at the Bates Motel, they are a team who start out together, split up and through the element of surprise are brought together again as bookends; Mother/Norman is caught in between them and his combination of personalities is reduced from two to one.

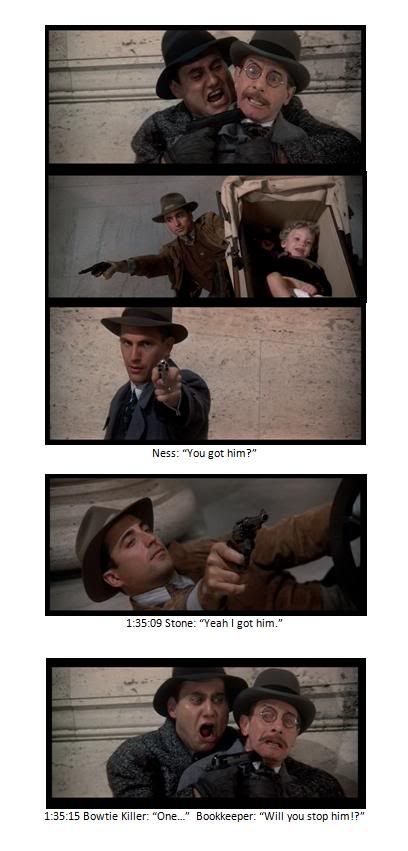

Regarding Stone and Ness in The Untouchables train station steps sequence, they are a team who start out together, split up and come together again to fight and triumph over adversity while standing at the threshold of a diagonal staircase in the climax of the train station sequence. In the final moments of this sequence, as the Bowtie Killer's right arm acts as a stranglehold while the left arm has a gun to the bookkeeper's head, he threatens to kill the bookkeeper unless they are both released from the standoff. He begins a count off starting at "one" with a pregnant pause. Ness commands Stone to "take him!" and he kills Bowtie and reduces that Capone pairing down to one. Stone finishes Bowtie's counting sentence by saying "two." The visual storytelling has shown architectural space being developed and explored and through editing, framing, and dialog we have been shown changes in shapes and the proximity of these elements and forms to communicate growth and advance the story.

The establishment of a deadly horizontal relationship of the bookkeeper's head caught in between an arm and a gun has changed into a new deadly horizontal relationship between Stone's gun and Bowtie's head.

The angle of the straight line has moved counterclockwise 90 degrees.

And at the end of the straight line is a circle that has become divided into life and death.

As Bowtie's head slips out of frame downwards, an artistic modern abstraction of bloody red color

is in evidence. De Palma the artist has thrown some paint upon the canvas for the audience and the characters to admire and comprehend. Bowtie has been zeroed out and we have to decide if Mr. Average, middle-American bookkeeper likes being an art critic, and we wonder if we see ourselves or the character in the canvas that he is standing too close to.

implication can be seen in the climax of the basement in Psycho, as well as Burke's activities in Blow Out.

There are plenty of well crafted films being made that show an understanding and appreciation of Hitchcock and suspense techniques and the use of subject matter that would appeal to him. Here are a few: Polanski's Frantic and Repulsion, Transsiberian by Brad Anderson, Sam Raimi's A Simple Plan. The films of the Coen Brothers are branded with their own personality and incorporate the best type of black humor, and tension and release familiar to fans of movies and Hitchcock, among them would be Fargo and their first film Blood Simple.

They all show a strong sense of dark humor, intelligence, film craft, dramatic tension, and sensitivity towards portraying human flaws and frailties.

They all show a strong sense of dark humor, intelligence, film craft, dramatic tension, and sensitivity towards portraying human flaws and frailties.

The visual direction and manipulation of actors and movement as graphic elements on screen are challenges that will always be faced and constantly addressed by directors and their production team. If the challenge is met and the idea is expressed successfully, the end product should be pleasing to the audience.

It is all about communicating a feeling and an idea in a meaningful way. If you don’t care for a type of art, or an instance of art created by a specific person, that does not necessarily mean that it is artless or poorly done, or that whatever a particular person does automatically means that it will be artless or poorly done.

In my opinion, there is an ancient idea that is still with us which tends to be discarded when it comes to most forms of pop culture - the complicity in the relationship between the artist and the audience. Who is responsible? If a picture doesn't work, has the artist failed in delivering the message or does the audience need to come around to the viewpoint and perspective of the artist?

I find that one of the main reasons that Brian De Palma’s films "work" for me is because of the technical virtuosity that is wrapped around and through the emotional content. There is always a sense of the fantastic lurking. They can be engaging, moving, and intellectually stimulating. The dark humor that I love in his films may not work for everyone in the audience, but like any fine art there are always things to discover if you are open to them.

The Steps

Once the sequence is underway inside the train station, the characters in the movie and the audience watching it will be prompted by off screen announcements regarding the Miami train on track 33 due to depart at 12:05.

The first section of the 9 ½ minute sequence lasts 6 minutes and it is focused upon slowly establishing tension. Time is expanded and continually stretched to the breaking point; the pacing starts out being long, whatever you see on the screen is occurring in normal time but the activity is innocuous and body motion is minimized. This is ramped up – gradually more and more people are coming down the stairs in a systematic pattern; through successive cutting back to the staircase, as people come down the left side, then the middle, then the right side, De Palma’s direction is pushing our eyes and attention to the far right wall where the final showdown will occur.

This also occurs when the editing and camera framing choices virtually bring the staircase to life as seen from above from Ness’s POV. The appearance and implied safety of the solid hand rails that delineate the staircase are rarely if ever used by characters in the sequence. In one case it ultimately becomes an obstacle to be overcome as we see a sailor shot and the impact thrusts him across the rail. A broken shadow pattern is cast upon the steps from the ceiling lights as they cast illumination upon the railings. The broken pattern is eye candy that tempts us even as it suggests inherent danger ahead. The steps will gradually inhabit and take up the majority of screen space in selected shots.

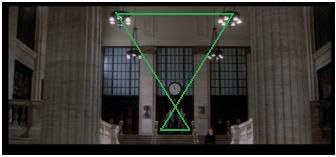

Four groups of six globes. Two columns.

Three sets of windows. Three sets of four doors.

One ticking clock.

Two men.

One boy.

An indication of numbering and relationships -

one pair moving together up the stairs

as one pair is being split high-low and moving apart.

Right now it seems pretty clear that I have an obsession with Chock Full of Nuts coffee and I'm nuts about the films of Brian De Palma. Art is not created in a vacuum. Everybody takes a turn creating the art or receiving the information from digesting what they see and then passing their thoughts along to somebody else. The Untouchables is not my favorite film by De Palma. My favorite De Palma film is still Blow Out.

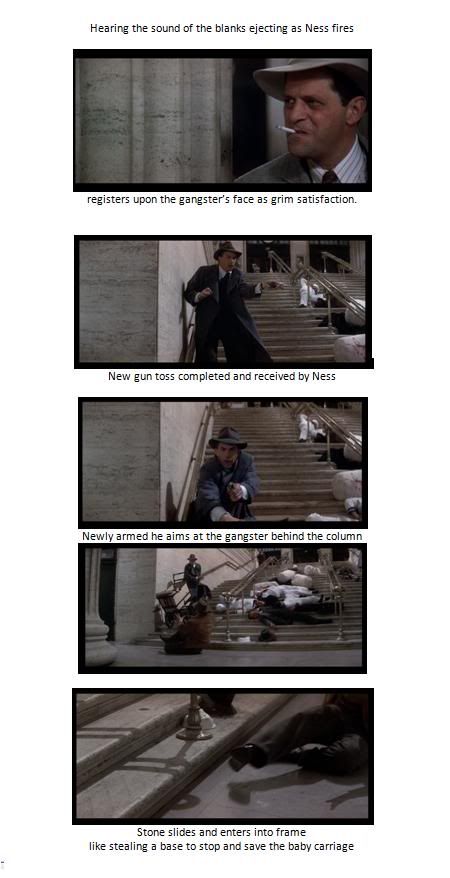

I chose to write about The Untouchables because I like it a great deal, and it was one of his most popular box office success stories. The train station sequence just happens to be one of my favorite De Palma sequences. The gun toss and sliding action of Stone is a superior cinematic moment. The gangster behind the column is killed and the audience is knocked out. The structure that is in place to support that moment becoming airborn is essential to enabling the viewer to feel it. The audience members who "receive" the gun as they see the subjective view point and embrace the ideas that go along with conveying it are the richer.

This might be really old news, but it tends to be forgotten when someone offers an opinion of how they react to an art encounter. We need to remember that the grammar and the methods and the techniques are all out there for everybody to employ, it is how an artist reframes the existing elements or ideas into new combinations that result in an art object for consumption to be accepted or rejected by a viewer. At this point in the history of film just about everything has already been done, and audience and filmmakers alike want to see something new - quite often that means an attempt at realizing the successful possibilities of recombining existing elements. It is that hard to do something new. Otherwise without realigning the elements and working within the constraints or limitations of what has been done, we would all give up on our movie fix. Forget it - that’s not gonna’ happen!

The train station sequence begins with the camera gently craning down and pushing gently through two columns as Ness and Stone enter into the train station interior space. They spread out high and low with Ness observing activity from a superior higher vantage point and Stone going off to a lower one after he is instructed to “Cover the South entrance.” The columns perform multiple duties. The columns provide support for the building structure but they are elements that indicate strength, they are vertical forms, they may be seen as inanimate parallels to Ness and Stone. Seen in a pairing, they are markers for a starting/finishing line running frame left and frame right. As the scene develops into a raging chaos played out upon the instability of a diagonal we crave a restoration of unity and balance and horizontal forms and vertical forms.

Four columns are inset

within a frame of two columns

as the cleanup crew of two men wipes down the floor.

Is it possible that this architectural framing is suggesting the idea below?

Is it possible that this architectural framing is suggesting the idea below?

Ness , Stone, Malone, Wallace - Four untouchables (columns in back)

Two are standing - Ness and Stone (columns in front)

and two have fallen - Malone and Wallace (two men cleaning floor)

By improvising upon the Odessa Steps sequence, a new irritating complication has been added into the story mix - the idea of having a mother struggling valiantly with her baby, a carriage and her luggage (emotional baggage, anyone?) trying to go up the stairs.

The visual suggested of a “tight squeeze play"

is reinforced by the idea of

the man and woman who easily descended the steps

only to find it difficult

trying to get through the gap

between the mother and the column at the foot of the stairs.

The visual motion of the mother sliding her baggage along the floor in an arc around the baby carriage plus the sound of the sliding adds to and builds upon the cleaning crew idea; it defines and marks where the visual payoff will be when George Stone will slide in front of the carriage to protect the baby near the end of the steps sequence.

The steps virtually come to life and become instilled with ferocious silent power. As the shots play out through editing, the steps literally take over the space within the frame as the mother and carriage are seen from the Ness POV.

Midnight becomes High Noon.

Is Kevin Costner now Gary Cooper?

the importance of the vertical and the maintaining of order are being visually suggested.

At this point in the sequence Ness is caught in the middle and must make a decision.

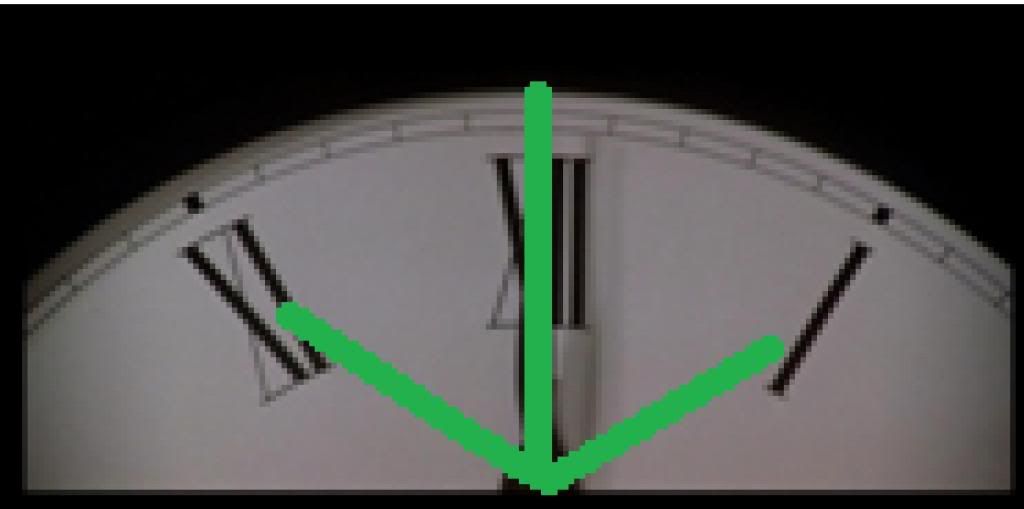

I like looking at the time on this clock face with Roman numerals because it shows similar shapes that the eye and brain can manipulate in different arrangements. They are X, I, and II.

We see:

- numeral ten - X - two times,

- numeral one - I - two times and then

- numeral two - II - is shown only once.

The message of the clock says midnight. It also suggests to me that the time is showing us the midpoint of a change in the Untouchables team.

and then the 4 became reduced by half and became (II).

Ness and Stone arrive in the station as one pair.

They split up and at the right moment,

by reuniting and working together they became one again (I).

the number 10 /ten and the idea of change or a reversal of fortune,

then that clock is expressing the telling of the time and alternative meanings as well.

We can also see that the eleven on the left plus one on the right equals twelve in the middle.

When you play around with digits in numerology you usually combine and reduce at the same time.

11 combined and reduced becomes 2,

12 combined and reduced becomes 3,

and 1 is already 1.

The total of 1, 2 and 3 is six.

We saw Stone shoot 1-2-3-4-5-6 shots in the Police Academy shooting range.

In the train station sequence we have seen an additive process of Capone’s men arrive as five thugs and one bookkeeper

We end up with three men and one baby, the Bowtie Killer counts out one and

Stone shoots him once and says two.

It goes on and on and on.

We should also address this indication of movement

I think that since we already know via dialog and visuals

that there is a 10 minute window available

to get the bookkeeper,

when we eventually look at the close-up the clock

on some internal level of the mind,

we can visualize the angle that defines the arc

between five before 12 and five after 12.

Through repetition of information and the progression of cuts

that visually brings the viewer closer and closer to the clock face,

when we take that subliminal information and visualization,

and we add it in to our available internal warehouse of clock associations,

and receive all of that into our minds,

the process provides what I believe to be this result below.

At midnight the two clock hands are together as one shape;

the minute hand slightly quivering to draw our attention to the importance of the midnight hour.

(For more great unsettling quivering motion see the car trunk in either Psycho or in Raising Cain)

If this doesn't work for another person - so be it.

I think that we see the clock and we envision the hand at five of and the hand at five after.

We envision a 60 degree arc and when we notice that it is midnight,

which is the halfway point inside of 10 minutes,

we create the arrow image.

This avenue of suggesting the direction is just another way of reinforcing what we already know from

the dialog and the situation, but it is perhaps an artistic choice either by the director or by me as the audience person, or both. For someone else that may not apply.

In an overall sense it should be our conscious responsibility to decipher whatever it is that we do see when we watch a film. We want to get lost in the film but we want meaning. There is an assembly line inside the mind subconsciously constructing meaning.If you are checking a cell phone or texting or your mind is elsewhere, then you or someone else as the viewer is multi-tasking in ways that ignore

or shut out the film.

Whose responsibility is that? Did the filmmaker hit a boring stretch? Is the content and presentation and concept compelling enough to engage multi-tasking between the screen messages and the viewer’s mind?

While the movie is playing, different messages are being sent and received both onscreen and off-screen.

Who is paying attention? What did you miss?

Obviously each audience member receives different cues in different ways and there is no guarantee that everyone will respond in a similar or exact manner.

However, if enough information or clues or signs or indications are provided to the audience in a variety of methods, through repetition, and differing levels of clarity, somebody at some time should get the message.

Trying to describe in words what the eye and ear process immediately is infinitely harder to do, and takes so much longer than an instant consumption of what is on the screen.

The ideas that I am trying to convey may or may not be there, or appear to be there, but I want to suggest the possibility, because I see it. In other words, we have reached a point in the train station sequence that is

the silent visual equivalent of a directive that was spoken to both the main character and audience alike

in a De Palma film that was released in 1984.

Do you remember the direction of the acting teacher to Jake Scully in Body Double?

"YOU'VE GOT TO ACT!"

So, let's get back to Eliot Ness.Having noted the midnight hour and prompted by what he has observed,

Ness decides to take action and he moves screen right.

In the moments just before Ness moves, there are suddenly four small globes (previously unseen) that are reflected in the background window glass behind him. They are aligned slightly askew but vertically - I feel this is not coincidental, or trivial, or a mistake - it is a small brushstroke on the canvas.

It strikes me as being a deliberate piece of visual shorthand that is a reference point that emits different bits of information: it telegraphs his intent; it indicates his direction and confirms his decision to make the move vertically straight down.

If it is not a reference to the unity and shared moral purpose of the four untouchables and the strength of vertical order, perhaps it suggests the "final four" persons that will be alive at the end of the steps sequence. The four lights aligned vertically are seen reflected in the window behind him and as such it is providing a consolidation of what he has seen, what he must do, the direction he must take and the moral character traits that he embodies.

The key here is what we see in reflection - conscience.

Is this a situation of GIGO? Am I overthinking things?

GIGO is an acronym that means "garbage in-garbage out" and it refers to entering invalid data on a computer and receiving faulty data back.

An acronym like GIGO is communicating four words in a new word made up of four letters - the first letter of each of the four words. Like my earlier mention of XYZ.

Just like GIGO or RADAR or SNAFU, I see an instance of visual storytelling - an acronym that contains meaning that can relate to character action or storyline. I see the line of four globes as suggesting the unity of the four untouchables and the action is moving downward and the story will progress from this action.

The application of information being relayed in this fashion to the audience in storytelling through visuals is one of the details that I find fascinating in processing meaning from within a film.

Or it could be nothing at all.

Having Ness take action by stepping into the stairwell to assist the mother and remove the mother/baby obstacle, is an instance where a character in a scene makes a choice that will either upend or correct his situation. His assistance puts him in danger, but it puts him in the right place at the right time to take control of the confrontation that is about to occur.

When he realizes that the sixth man is behind him at the door and that he is surrounded, he turns away from his morality and faces his mortality by firing the first shot that sends the mobster backwards through the plate glass of an entrance door and with the shattering of glass and the burst of a tommy gun, the tension has reached the breaking point, all hell is now loose, the gunfight has started and the second half of the sequence has begun. To me, among the strongest of the procession of images in the sequence is that of Ness in slow motion pulling the mother behind him as he fires his shotgun - this is a verification that he is making the transition from the “Poor Butterfly” persona into a tough lawman ready to meet evil and fight his way down into the trenches.

Once we reach this breaking point, as we go forward the timing of edits is shorter and compressed, the visuals are explosive and active, in both normal speed and slow motion; we experience time being bent and altered in a more impressionistic style.

The Untouchables Train station steps sequence

Listed below is an approximate breakdown of the main edits.

(Depending on the pc program I used for play back or my error, there may be a discrepancy in time listed)

Begin First half – Six minutes

1:26:23 sequence start

1:27:15 baby cries

1:27:22 lullaby music starts

1:27:27 1st announcement - Your attention please of train departing to Miami at 12:05 track 33 all aboard

- 9 second gap between audio announcements-

1:28:06 2nd announcement - Your attention please of train departing to Miami at 12:05 track 33 all aboard

- 75 second gap second gap between audio announcements-

1:29:21 3rd announcement - Your attention please of train departing to Miami at 12:05 track 33 all aboard

- 44 second gap second gap second gap between audio announcements-

1:30:04 4th announcement - Your attention please FINAL CALL

1:30:33 CU clock midnight

1:30:45 Ness assists mother with child

1:31:08 Mother: “You’re such a kind gentleman to help me” “I wasn’t sure we’d make it “

Two Capone gangsters enter on right top of stairs descending down to the bottom,

each man takes one side of the steps left and right:

1:31:28 Mother to her baby “Isn’t this fun?”

Background office door reads “222” as Ness ascends the last stairs at the top

1:31:34 Mother “Thank you again this is so wonderful”

Ness notices a new Capone gangster to his right at the top of the stairs

1:31:34 Door “222” again in frame left with Ness frame right

1:31:49 Man and bookkeeper arrive

1:31:59 Mother “Thank you very much I’ll take it from here.”

Sixth man arrives behind Ness – we see him – Ness does not

1:32:02 Ness now aware of 6th man - he is surrounded

1:32:05 baby’s cry

He looks back to baby /cut to move in on 6th man’s face.

1:32:16 Ness turns to face the crisis and the 6th man

1:32:21 Ness raises shotgun

Breaking point – at approximately the six minute mark

1:32:23 Shotgun blast/shattering of glass indicates the breaking point has been reached

- The tension is being released and escalated at the same time.

- Time manipulation through editing and camera framing.

- faster cutting / alternating between normal and slower fps camera speed.

Begin second half

1:32:26 Stone hears the gunplay realizes he must return

1:32:31 Ness releases his hand from the carriage handle.

1:32:34 Carriage moves forward to precipice of stairs

1:32:38 Ness pulls mother behind him as he is about to shoot

1:32:39 second Ness shotgun blast takes out a gangster

Background of office door clearly says “228”

1:32:46 Bookkeeper crouches machine gun burst/gangster shooting machine gun/

1:32:47 Framing on gangster with tommy gun as he is shot from behind, framing changes as body falls

forward out of frame revealing Stone hi above through an emphatic zoom in, end of the new framing

visually shows Stone is a tight squeeze of vertically clear space

1:32:49 Stone framed tightly pointing gun from between two pillars

1:32:55 Mother silently mouths the words “My baby!”

1:33:10 Carriage begins descent down first step

1:33:17 Stone runs with a gun in each hand to frame left to get back to the bottom of the staircase area

1:33:21Ness throws down machine gun switches to hand gun

1:33:25 Ness runs to cover carriage descending last portion of steps towards gangster with gun at bottom

1:33:31 Gangster fires at Ness

1:33:32 Ness returns fire

1:33:33 Gangster midlevel right steps shoots at carriage and Ness

1:33:35 Ness fires at gangster at bottom of steps who has hidden behind the column.

1:33:39 Sailor takes a hit

1:33:42 Ness and gangster behind column exchange shots again

1:33:50 gangster behind column ejects gun cartridge to reload

1:33:51 Ness fires /cut to tighter side shot of Gangster’s head reacting to sound of shot behind column

Camera tilts down to show him shove a new bullet clip into handgun.

1:33:54 Ness shooting blanks/ carriage almost to bottom

1:33:58 Gangster smiling/Ness looking/ Stone arriving

1:34:00 slow motion gun toss towards Ness subjective camera frame

1:34:05 Ness with a new gun from Stone aims at gangster

1:34:07 Ness shoots takes out gangster emerging from column

1:34:08 floor level angle track in on Stone’s hat as he blocks/stops baby carriage

1:34:12 C’mon let’s get out of here fifth and last gangster standing commands bookkeeper.

1:34:16 Angle on Baby’s face- safe lullaby music box music returns

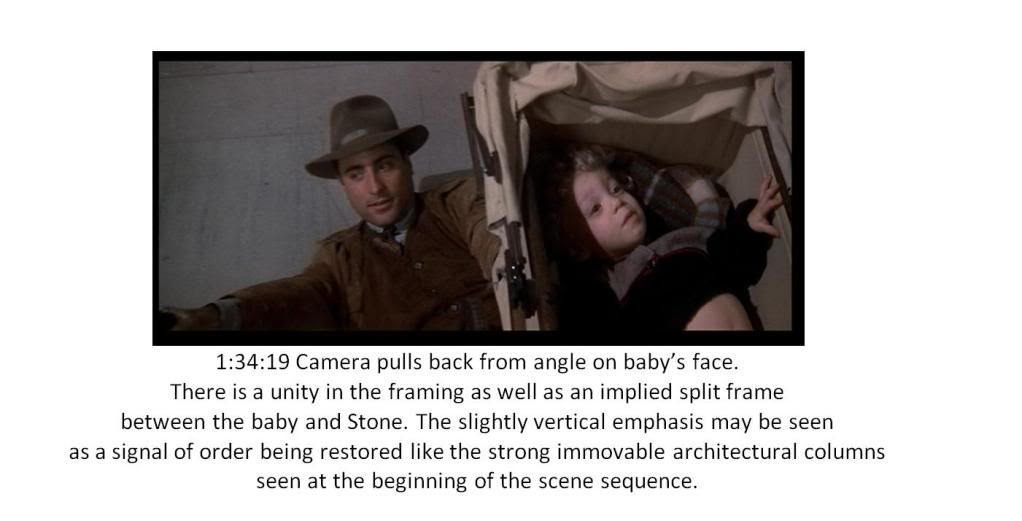

1:34:19 Camera pulls back to reveal implied split screen framing Stone on left baby on right

1:34:11 Dialog is resumed “C’mon let’s get out of here”

1:34:22 Bowtie Killer’s neck hold on bookkeeper’s head

1:34:26 three shot Ness Stone and baby by handrails

1:34:28 Mother shouts “My baby” and you can hear the words

1:34:35 I’m walking out with the bookkeeper

He dies, he dies and you ain’t got nothing (double negative which means Ness does have something)

You got five seconds to make up your mind

1:35:00 I’ll tell you what you want to know

You got him?

1:35:09 Yeah I got him

1:35:15 “One!” “Will you stop him!”

1:35:23 Bowtie inhales as he is about to say two/cut to Ness “Take him”/ cut to gunshot

1:35:27 Stone says “Two”

1:35:30 Bookkeeper’s eyes open as Bowtie Killer’s mouth spews a volcanic stream of blood

1:35:37 Bookkeeper turns and looks down as the sound of Bowtie Killer’s body hits floor

1:35:39 Ness watches bookkeeper’s dismay at having avoiding death and

seeing Bowtie Killer dead at his feet.

1:35:40 low angle on bookkeeper framed against ceiling cluster his hat allows 4 globes to be visible

He moves and now 6 globes are visible

1:35:42 Bookkeeper turns to react to seeing Stone

1:35:46 Stone cocks his gun and holds the wheel of the baby carriage awaiting the next move

1:35:55 cut to Int. courtroom

So – the start of the second half is 1:32:26 and it ends at approx 1:35:55

The second half totals approximately 3 minutes and 30 seconds.

This can be broken down into 3 minutes time until the gunshot @ approx 1:32:25

Then a final 30 seconds of the bookkeeper surviving the purge: a shaken and whimpering man standing alone.

So in total we have gone nine and a half minutes in three steps:

6 (minutes) changes over to

3 (minutes) which changes to

½ (30 seconds)

We have all been conditioned to respond to thirty seconds as a unit of time because of the years of commercials that we have been subjected to. On a subliminal level, if the train station sequence has worked well for the audience, the last 30 seconds should be a substantial payoff that will resonate into the courtroom sequence and the final 30 minutes of the film.

More Numbers

• The film’s total running time is 119 minutes which can be rounded off to 2 hours or 120 minutes.

• The train station sequence begins almost 90 minutes into the film or 30 minutes before the end,

so this sequence within the total timeline of the film is positioned at a transition point of a 3-to-1 ratio.

Here we see a visual relationship and alignment of two and three which will change to a ratio of three and one after the takedown of the Bowtie Killer.

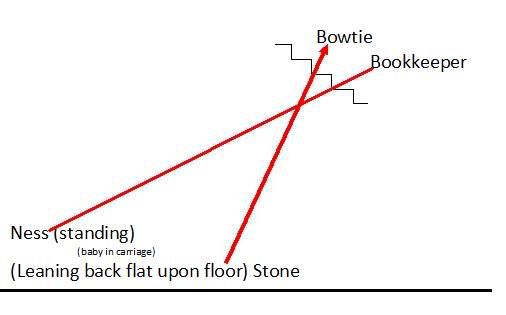

As the audience, if you were to visualize and imagine placing yourself inside the train station space at the bottom of the staircase behind Ness, the baby and Stone and seeing the Bowtie killer standing on the steps left of the bookkeeper, there is an implication of an X being reinforced and underlining the reversal of fortune and power if you will.

By envisioning and drawing a line between Stone and Bowtie, and Ness and the bookkeeper, that would create the X.

So when we first viewed the interior of the train station

as Ness and Stone entered the space,

the X- hourglass- pyramid balancing act

which was implied by the framing of them against the architectural details,

has been repositioned into

a skewed placement across the steps and between the walls.

The survivors at the end of the train station sequence are literally the

"last men standing” as the mother is unseen but safely out of frame.

There are four characters left. It may be deliberate structuring,

or it might be coincidental that when the sequence has finally played itself out,

the four characters can be seen in a 3-to-1 ratio as well.

The last edits of the sequence are the three remaining men in a visual standoff with the baby noticeably out of frame.

(Screenshots play left to right)

The bookkeeper against a soiled wall reacts to Stone who is using both hands for control.

The bookkeeper reacts to Ness in front of a clean wall and having the last look

In the final positioning, a moral balance - a state of equality has been achieved because

those who are “left” are left alive and whoever is on the “right” is on the side of right.

We have three men and a baby, and this is not the American remake of the French comedy starring Tom Selleck and Steve Guttenberg. The conclusion of the train station sequence shows a restoration or order and a melodramatic transformation of our main character. The teamwork and sharpshooting talent of George Stone along with the resilience of Eliot Ness has made Ness into a man who can continue to champion law and order and family and morality. He has not abandoned his childish ways; he has adapted to his environment and made room for self-preservation by successfully fighting violence by employing violence.

The final shot of Ness observing the situation means that he has the last word and balance has been restored, at least for that moment in the film.

When you examine narrative film and cinema from a western cultural perspective where we learn to visually read written words left to right, one of the traditional ways of understanding meaning that is being conveyed with regard to screen movement is an option to be employed in the construction of the film.

When you are moving screen left you are potentially watching or indicating

obstacles or barriers or the sense of space being "closed."

When you show movement screen right

there can be an indication or understanding of openness or a sense of space and freedom.

An example of movement screen left as a barrier or obstacle for the story can be seen in Psycho when the characters are constantly "stopped" by the barrier of Norman and / or the corner post of the Bates Motel exterior. Even Norman is seen momentarily stopping as only he hears a silent call to a personal understanding of what he must do. The camera placement adjusts during the move so that as he exits frame left, the camera stops to frame a corner vertical line.

When we are shown scenes at the Bates Motel, only Norman early on shows the ability to move freely to the right until Lila arrives and Sam provides a barrier to Norman.

As the Psycho story advances and as our journey towards clarity is being achieved, the framing of the exterior of the motel becomes wider, and the sky progressively changes becoming more clear.

The tragic climax of Karel Reisz's Sweet Dreams is a camera pan left that shocks the audience when the plane carrying Patsy Cline crashes into an unforeseen solid mountainside that stops the plane and the pan.

At the end of Kubrick's Full Metal Jacket the camera is moving in tandem with the men who are marching screen left as they sing the Mickey Mouse Club theme into the night. The story ends for the viewer, but for the Marines, the same struggle with maintaining sanity as they transform themselves into mean, green killing machines will continue to be an ongoing dramatic burden in the nightmares yet to be.

Back to Ness, Back to the wall

Given this perspective, the placement of Ness and Stone screen left can be seen as having their backs

against a wall (or an obstacle) but facing right.

The bookkeeper and Bowtie Killer have their back against the wall, too. But they are looking

left and facing an obstacle or a barrier that cannot be overcome.

Visual arithmetic at work?

Perhaps we might see the framing of the final shots in the train station sequence below as visual shorthand with numbers in relation to the story.

FOUR globes are visible in the frame grab shown above. As the bookkeeper moves his head,

we see two more globes are revealed in the cluster of lights above as the shot continues.

Below: A framed relationship of cause and effect.

Is this a suggestion of

six-four-two-one-zero?

Above: SIX visible globes.

Within the same shot we see a transition from four to six in the lights.

Is this just a nice shot or is there a meaning, a suggestion of something more?

Perhaps this is a visual echo of a revolver barrel.

The difference between four and six is two

Two is the last word spoken by Stone following the killshot

Four plus six is 10 the number of minutes available to catch the bookkeeper.

The digit between 4 and 6 is 5

and 5 can mean death as it does later when Nitti is pushed to his death.

In seeing a movie, the graphic shapes that we perceive may be observed as only abstractions.

They may or may not be seen as meaningful.

If they are evaluated as being meaningful, there is at least one meaning available for discovery,

If they are evaluated as being meaningful, there is at least one meaning available for discovery,

but they can also be placeholders for the audience to choose to work with or ignore.

We can contemplate, ignore or plug meaning into them as needed.

We can contemplate, ignore or plug meaning into them as needed.

Kind of like what I 'm doing now. (Ahem, throat clear)

Numbering from high upon the courthouse rooftop

We know that in De Palma’s film Carlito’s Way when Carlito Brigante contemplates the youthful mistakes that he wants to abandon as an adult, he allows Benny Blanco to survive a trip down the stairs into the back alley, and Carlito will pay for this gesture with his own life.

As Eliot Ness moves forward through the story he is constantly struggling to maintain his moral standards with his conflicted feelings of using violence.

We recall Ness firing a warning shot into the air in the first botched warehouse raid that was followed by the newspaper photograph titled ELIOT NESS: (Poor Butterfly). Later on he throws down his gun in disgust (in the Canadian raid where he kills a man), and he tempers his action when his hands move the shotgun down out of frame as needed (in response to realizing that the lovers in the train station are a false alarm), and finally when in the heat of the train station shootout, he throws down his empty shotgun to switch to his loaded handguns.

When the story line moves on to Capone’s trial and Ness pursues Frank Nitti up a winding staircase onto the rooftop of the courthouse, he eventually is in a position to extend compassion to Nitti. As Nitti hangs in the balance by a rope on the side of the building, Ness ignores his initial instinct to shoot him, and gently returns the trigger to a resting position, pulling Nitti up to safety upon the roof.

When Nitti remains true to his lack of character and refuses to show respect to Ness by taunting him with an insult about the killing of Malone and how his death sounded like a pig squeal, Ness becomes an executioner and pushes Nitti off the roof. At this point in the movie we can see how Ness has become larger than life. Ness does not aspire to be powerful like Tony Montana or Carlito Brigante, but he has touched upon that feeling and ability that is within us all. It allows him to become just like the hard, silent and angry staircase which filled the screen when he looked down upon the mother with her baby.

His rage has pushed himself over the edge and he has realized that feeling by pushing Nitti over the edge. He stands tall and centered after killing Nitti; he dominates the screen as he is framed against the sky with a Godlike vantage point from the roof.

The cut from Ness looking down

to the POV of Ness looking at Nitti's landing

is an expression of numbering

where we can consider

life and death

in the same relationship that exists

between one and five, and five and one - each relationship has a different and opposite outcome.

- restraint and relaxing the trigger finger and then extending a hand in consideration - is life

- lack of restraint in one man using his hand to push off and punish another - is death

Having survived the staircase sequence in the train station,

at this point he has mastered a balancing act upon the diagonal.

Eliot Ness has become like the train station staircase -

a powerful force that is centered and dominates the screen frame.

The power of 1 -

the trigger finger that allowed Nitti to live when Ness uncocked the gun

and offered him a hand to climb up on the roof,

has been overruled by the power of 5 (the fist).

the trigger finger that allowed Nitti to live when Ness uncocked the gun

and offered him a hand to climb up on the roof,

has been overruled by the power of 5 (the fist).

His emotions have boiled over, and Ness has allowed his heart to rule his head.

From the Ness POV- the cars are aligned in a jagged stair-step sequence - a slightly diagonal line segment.

As Nitti's body is violently cast down through the car roof to his long overdue death,

the fifth car that has become Nitti’s coffin is akin to a visual exclamation point as it follows the first four cars.

The initial inclination to kill Nitti was overruled by Ness and his code of ethics.

As Nitti's body is violently cast down through the car roof to his long overdue death,

the fifth car that has become Nitti’s coffin is akin to a visual exclamation point as it follows the first four cars.

The initial inclination to kill Nitti was overruled by Ness and his code of ethics.

Nitti pushed Ness too far with his banter.

Cause and effect - a visual indication of the power of the four Untouchables upon Nitti.

This visual of four next to one totaling five may be seen

as a new way of stating or echoing or restating the relationship between the forces of

Ness to the left and Capone to the right which we observed in the train station sequence.

Four plus one = five = death.

Ness and Nitti are two equal forces in opposition who struggle to dominate each other.

It is eventually resolved when they are combined and reduced "by the numbers"

and the connection between them results in two becoming one.

The long line segment that connects Ness and Nitti

runs from the top of the sky to the ground and the street far below.

It is a statement of the idea of strength and dominance - the vertical.

This invoking of numbering 1,4, and 5 can be traced back to Hitchcock's Psycho. While no one (so far) has been able to reach that level of mind-blowing power over an audience as Hitchcock was able to do in the whole picture and specifically in the basement given the culture of 1960 and audience sophistication, the inherent power of using those numbers can be employed again in a different way and De Palma, in my opinion is doing that in a scene such as this.

Brian De Palma is one of my favorite directors because he truly has a personal stamp and sensibility that filters his interests, his influences and the material into cinematic works of art that satisfy and entertain me as a film fan. By exploring and studying his art we all can learn from his visual style of communicating. He really excels at providing visceral experiences to his audience. His films speak for themselves, and we only need to perceive it, but some viewers don’t see the beauty and perhaps they can’t be bothered with processing the information. The interviews of Brian De Palma that I have read or watched indicate that he is always concerned with avoiding what is boring wherever possible and emphasizing what is visually compelling and inherently cinematic and this depends on using the timeless great ideas that originate in life, the ideas that are awakened within him or exist outside of him and are reinterpreted and conveyed to the audience. For the satisfied fan, they are employed and delivered in the combination of the music, the cinematography, the editing, the writing and the direction with the same accuracy as George Stone firing a gun.

I would imagine that as a fan of his work, I am not alone in feeling the musical emotional connection to his films. The Black Dahlia score is really superb and sublime. Among the vivid moments that I can recall in memory or through repeated viewings are: the call of the hero as the music sounds out when Jack Terry runs down from the bridge and dives into the water to save Sally, or the beauty and tragedy of watching Jack Terry running in slow motion up the stairs to save her once again in Blow Out; Rick Santoro confronting the aftermath and terror of an assassination at ringside in Snake Eyes; the slow deliberate camera movement that cranes down in a serpentine motion that curves and zooms in to a close up of the theatre classified section in Body Double; the transformation sequence in Dr. Elliott’s office in Dressed to Kill, and the amazing music by Ennio Morricone in The Untouchables. These are just a few of the many movie moments that I relish in De Palma films.

Brian De Palma has been really blessed in being able to work with the best composers doing some of their finest work. Pino Donaggio: Dressed to Kill, Blow Out, Body Double, and Raising Cain. Patrick Doyle: Carlito’s Way. Ennio Morricone: The Untouchables, Casualties of War, and Mission to Mars. Bernard Herrmann: Sisters and Obsession. Ryuichi Sakamoto: Snake Eyes and Femme Fatale. Mark Isham: The Black Dahlia. John Williams: The Fury. This is an astonishing number of memorable, emotional, and genuinely musical soundtracks.

In music Tony Bennett will be forever linked to his version of “I Left My Heart in San Francisco.” Guitarist Jim Hall has been revered for his interpretation of “All the Things You Are.” While those performers did not author those particular songs that they continue to perform, those works can be identified as “belonging to them” or as being their song due to their unique artistic rendering. When an artist delivers an interpretation of another person’s art even if they did not write the song, their viewpoint and artistic presentation of the idea makes the art become a recreation in their own image as if they had originally written it and in a sense they have. As the audience accepts or rejects the new creation, they come away enthralled or appalled.

In some sense, I believe that the true fans of Brian De Palma, the ones who “get it” understand that on one level of his many abilities as a filmmaker, he plays with ideas like a musician playing the changes of chords and improvising uniquely upon them in a song performed in his own voice.

When it works, it is magnificent and deserving of wider appreciation by all film lovers.

I had offered a short comment to the Geoff Songs De Palma a La Mod site back on August 2nd when Geoff had posted a link to the John Kenneth Muir review of The Untouchables.

http://www.angelfire.com/de/palma/blog/index.blog/1376103/mainstream-masterpiece/

I made a short comment and Geoff had added the following:

“Yeah, I think people misunderstand that De Palma expects people to notice the other films he is referencing (it's more like "riffing on" rather than "ripping off"), but then he takes them to unexpected places.”

I couldn’t agree more.

September 16, 2009

Part Three This is where I declare that I DIG DE PALMA ! ! !

I guess that what I'm trying to say regarding De Palma and numbering and

The Untouchables train station sequence is that:

I dig De Palma.

That's clear, isn't it?

It's as simple as that.

I admire him and his ability to communicate content so well in his own unique way.

As a storyteller, the conception and execution of the set piece in the train station

to me is miraculous- the payoff of the gun toss as a part of the overall trajectory

of the scene just makes me smile and shake my head in agreement with the magic that is

being performed when you watch the film.

That's really the way I feel about what he creates.

It works for me.

Before I close out my viewpoint, I wanted to look at something else.

This is how the steps were visually presented in the film at the beginning of the sequence.

We can agree that this framing and the action within it, shot head on

shows the steps divided into vertical thirds in a state of normality and balance.

Looking at it now, I realize that we can also see the steps as a vertical division into fifths

The steps in thirds framed within the bookends of the columns makes five.

Five minus three is two.

We see two columns, two sailors, two untouchables...

Elemental forms expressed as 2-2-2.

Two pairs in movement: one pair is together, one pair is splitting apart.

One pair is static and immovable.

What if we subtract two from five?

We get three which returns us to the steps.

If you examine the frame grab below, and you mentally divide it

vertically in thirds, (which is the same way that we remember seeing the initial visual presentation of the steps), we can see that a contraction of the screen space is revising our perception of how we saw the original symmetry of the steps.

This new framing by the camera is showing us a different kind of squeeze play this time.

This presentation of visual information is the next step in honoring what has gone before, and what is to come.

There has been another conversion, and it is related to numbers.

1) Visually the space that we associated with the first set of steps on the left side is now a solid wall.

2) The first set of steps that Ness is descending has now taken the place within the screen frame

of the second set of steps.

On a psychological visual level, our perception of the danger has been increased because it appears to be more uncomfortable to view Ness as having less open space.

We also associate the second path of steps with the massive death heap of sailor bodies piled high. (Just after their arrival from the set of the Battleship Potemkin.)

He is also pointing a gun at the audience and his aim is just slightly off of a direct path to us

because he is aiming at something that is very close to the audience. A tighter space is being created for the audience to inhabit - it is a virtual space that exists simultaneously behind us and in that area

that lies between our seats in the audience and in front of Ness.

3) The third set of steps has been virtually pushed out of frame.

When the showdown concludes along the relatively open path that exists along the North to South line axis (which is perceived as being vertical), the battle will play out East to West (which we perceive as horizontal) between two walls.

Look again at the screen grab and you can see that the new framing of Ness also shows him centered within the entire frame.

However, if you (once again) consider the vertical division of the frame into thirds, he is just to the right of the wall's edge which suggests to me visually that he is at a disadvantage.

The obstacle/ barrier idea that can be associated with movement toward the edge of the left of screen is in effect; the left vertical side of the perimeter of the screen frame has grown wider and moved to the right and into the frame taking up a third of the space.

This is similar to our understanding of the steps which grew horizontally "wider" in the train station when viewed from above - and eventually consumed the screen space.

If we look at the middle and right side vertical thirds of the frame, we see that Ness is on the left of that frame within a frame.

Now we are back to playing with 1-2-3 with the frame as vertical thirds

with Ness being 2 (in a space along with 3) and 1 being the blank wall.

When Ness and Stone eventually triumph over adversity and gain the bookkeeper not only will the experience be behind them, so will the wall.

Just look at the screen grab of Ness in the last frames of the entire sequence.

We can see that the appearance of the wall in the left third of the frame has our attention,

and by being brought to our attention it acts as a force that influences the character and the viewer by increasing visual and psychological tension.

It is also a re-introduction of an existing visual element that stands out from the character, performs the intended function, and then becomes associated with the strength of Ness and his squad in visual unity.

Unity: Stone and Ness, Ness and Column, Stone and floor, Ness and wall

Just like the clock hands at 12 o'clock that indicate unity and strength, the form of the vertical column that can be seen as a parallel to either of the Ness or Stone characters has become unified with their counterpart.

The arc of the scene sequence has been a transformation of character and action.

Our visual perception of Ness and the elements that exist in the space around him have been transformed and expanded. He started out standing next to Stone as one of a pair of two small vertical visual lines just below the clock.

The visual presentation of Ness, Stone, the wall, and the column as elemental forms are established and manipulated and transformed as the story has been told.

Our understanding of what has changed in the characters is explained to us visually through their actions and by their placement within the screen space as forms and in the proximity of each form to other forms.

The forms can be shown as being in a state of opposition or of being polarized.

HIDING

The gangster hides from Ness behind a column.

Note the framing which reinforces the design of the column

with four (a number we associate with the members of the Untouchables) visible vertical lines.

Compared with the screen grab above where it appears that

Ness is being pushed aside to the right as the wall intrudes,

the tide seems to be turning towards favoring Ness

because visually the framing of the gangster below

is experiencing a squeeze play of his own:

the screen space is more compressed

and the majority of the space is occupied by the column

with four distinct vertical lines and the associated power of the Untouchables acting in unity -

four becomes two becomes one all at the same time.

NOTHING TO HIDE

Forms can become harmonious as they are at the end of this sequence when they are finally brought together into unity. During the sequence upon the steps of the train station, the character of Ness and the parallel form of the column have both been expanded. The thickness of the column as a vertical line has been developed and expanded outward into an entire geometric plane, a solid field that covers the screen as it now becomes the background against which Ness stands out at the end.

Brian De Palma knows how to use film technique and his masterful use of subjective point of view shots intercut with objective viewpoints really brings vibrancy to his films - especially this one.

The train station sequence is a set piece that is a showcase for filmmaking. The editing is outstanding and the ideas are electric and alive; a virtual rollercoaster ride that brings the audience right into the screen.

My exit line is:

Anyway you see it,

is the way it is...................................................until you see it differently.

So who's driving the vehicle on the road to perception?

When we watch a film, each of us may get on or off the story road at a different access point only to return again to the path at a later time during the viewing or upon a returning view when we watch again - we are all trying to reach the same destination.

The intent is to communicate a road map for the viewer and when we do get to "the end," hopefully we will have had a pleasant trip even though each of us sees different things in a different way.

Then we go back and do it again.

Filmmakers practice a craft and technique of communication with everyone sharing the same

toolkit and limitations. It is up to the artist to create something of value and it is the responsibility

of the audience to perceive and judge what they have been given.

It's all there on the screen.

All you have to do is open your eyes, your heart, and your mind.

That means you! That's right, you there!

That casual fan or critic that "watches" a film and thoughtlessly,

and carelessly tosses my main man BDP off to the side of the road.

What's wrong with you?

Randy Aitken

Originally posted September 16-17, 2009

last updated and revised 10-2-09 11:07 PM

P.S. Let me ask a musical question as if it were my reworking of the song Do You Hear What I Hear?

Do you see what I-ce?